Canal Saint-Martin beyond the postcard : A brief History of Paris's iconic waterway

Behind the tree-lined banks and café terraces of the Canal Saint-Martin lies another Paris. This 4.5-kilometer waterway, stretching from the Bassin de la Villette to the Port de l’Arsenal, tells the story of a city shaped by ambition, innovation, and constant reinvention. As a local architect and guide, I reveal the hidden layers of history and design that make this canal a living archive of urban transformation.

HISTORY

8/8/20257 min read

Walking along the Canal Saint-Martin, I often pass people who stop to photograph its postcard charm. They see the picturesque; I read the history.

As an architect and urban planner who has lived in this neighborhood for years, I decipher the superimposed layers of Parisian time in every cast-iron bridge, every lock, every facade.

The Canal Saint-Martin is a place we think we know: its iron footbridges, tree-lined banks, postcard cafés. Yet behind this bohemian charm — the terraces, the trees, the slow afternoons — lies a dense, technical and poetic history, shaped by labor, gentrification, and centuries of transformation. Rooted in local life, the canal remains emblematic of Paris itself. It thrives on contrasts — in its winding path and its shifting purpose.

Stretching 4.5 km from the Bassin de la Villette to the Port de l'Arsenal, the canal has carried 200 years of urban evolution. Beneath its cobblestones and reflections, Paris has invented, forgotten, and reinvented its infrastructure.

Here are five key chapters — all still visible today, if you know how to read them. Let me help you situate these layers in the canal’s long urban story.

1. The Origins : A Cure for a Sick City (1802–1825)

Why dig a canal at all?

In 1802, under Napoleon Bonaparte, Paris faced a public health crisis. The Seine was polluted, wells were unreliable, and epidemics like cholera and dysentery were spreading. To bring clean water into the city, Napoleon ordered the construction of a canal system fed by the River Ourcq, 100 km northeast. The project was entrusted to engineer Pierre-Simon Girard and funded by a tax on wine. However, construction would not begin until 1822.

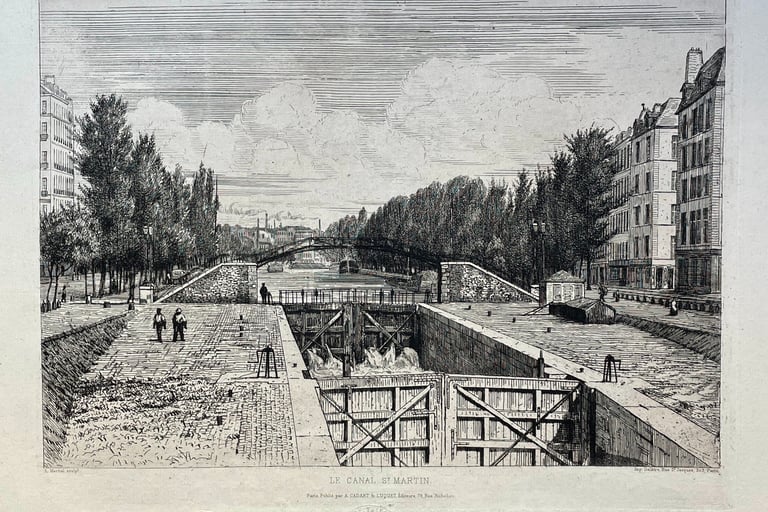

The Canal Saint-Martin, completed in 1825 and inaugurated by Charles X, was the final leg of this system. It supplied fountains, cleaned streets through water flushing, and provided drinking water to slaughterhouses and working-class neighborhoods. It also became a vital freight corridor for wine, grain, wood, and construction materials.

What to look for today

• Rotating bridges at Rue Dieu and Grange-aux-Belles: these pivot horizontally to let boats pass. Their exposed mechanics and stone abutments bear the marks of time.

• Locks : nine in total. They regulate water levels and allow boats to navigate the canal’s 25-meter drop between the Bassin de la Villette and the Seine.

• Lock-keeper houses : modest buildings beside the locks, built in the early 19th century. They once housed both canal staff and their equipment, serving as homes and workstations for lock keepers.

2. Hidden Beneath the Boulevards (second half of the 19th century)

In the mid-19th century, Baron Haussmann, under Napoleon III, launched a vast modernization of Paris. His plan for wide, straight boulevards clashed with the canal’s open path, which he saw as an obstacle — especially to the creation of the new Boulevard du Prince Eugène (now Boulevard Voltaire), which he didn’t want interrupted by a bridge.

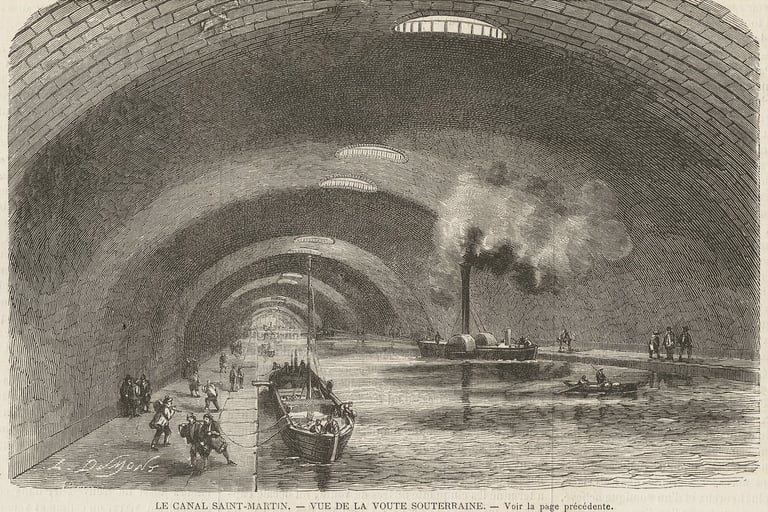

To preserve the boulevard’s continuity, nearly 2 kilometers of the Canal Saint-Martin were buried beneath a vaulted tunnel built between 1859 and 1860 to allow the canal to pass beneath the newly created boulevard. This underground section later made possible the construction of Boulevards Richard-Lenoir and Jules-Ferry above it.

To maintain navigation, the canal’s level was lowered by 5.5 meters, and a system of ventilation shafts was installed. The underground section remains navigable today.

What to look for today

• Street curvature : both boulevards follow the canal’s original meander — a subtle trace of the buried waterway.

• The vault : it is visible from Square Frédérick-Lemaître, where barges slip into its shadowy entrance, seemingly swallowed by the city’s depths. This hidden world is navigable by boat—Paris Canal and Canauxrama offer cruises through the underground passage, where light filters in through overhead oculi.

• Haussmannian façades : built after the canal was covered, their alignment and rhythm reflect the new urban order imposed above the hidden infrastructure.

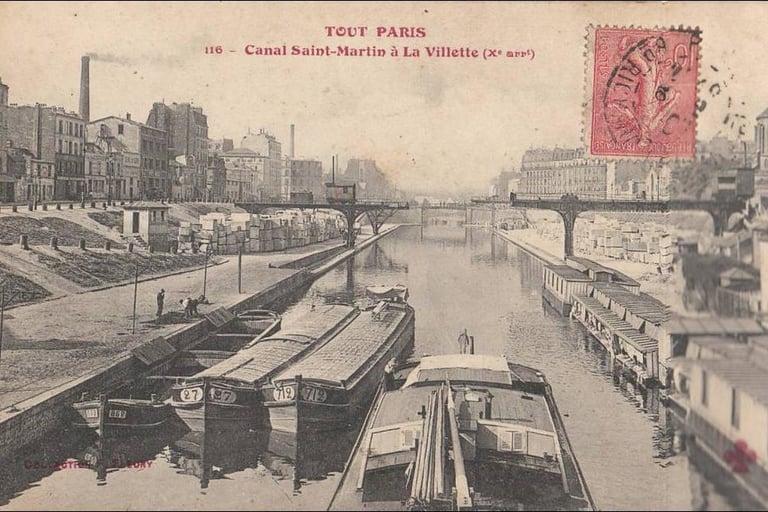

3. An Industrial and Commercial Artery (Late 19th Century – 1930s)

From the late 1800s to the 1930s, the canal became an economic artery for the capital. Barges transported coal, leather, textiles, and wine. Warehouses, factories, and modest housing lined its banks. The area was densely populated and industrious, with a strong working-class identity.

The canal was alive with constant activity — boats tied up side by side, workers unloading heavy cargo, and the air thick with coal smoke, creaking wood, and clanking chains. It was the heart of a hardworking industrial neighborhood, marked by noisy labor and everyday life.

The novel Hôtel du Nord (1929) and its 1938 film adaptation by Marcel Carné captured the lives of the canal’s residents — particularly the tenants of the modest hotel — and helped cement the canal’s place in Parisian cultural memory.

What to look for today

• Hôtel du Nord façade at 102 Quai de Jemmapes : modest and symmetrical, with its original signage and proportions still intact.

• Exacompta Factory at 138 Quai de Jemmapes: housed in a former power plant built in 1895 by architect Paul Friesé and repurposed in 1928, it now serves mainly as office space within a complex that still produces registers and stationery — a rare example of living industry in central Paris.

• Point Éphémère’s at 200 Quai de Valmy : built in 1922 as a materials warehouse. Its concrete frame, steel beams, and loading bays remain visible.

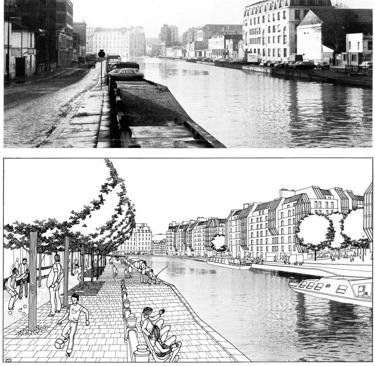

4. Decline and Disrepair (1950–1980)

After WWII, canal freight declined as road and rail transport took over. As factories closed and warehouses emptied, the quays became dominated by cars and parking lots. The canal, cut off from city life, felt unsafe and unwelcoming. In 1963, officials even proposed filling it in for a highway — a plan abandoned in 1971 thanks to local resistance.

Still, some change occurred. A few residential buildings appeared along the banks, where industrial gaps had opened up. One example is the Résidence Grancanal (48–58 quai de Jemmapes), built in the 1970s, with modern towers on pilotis typical of the time.

These rare interventions, driven by vacant land and a modest interest in canal-side living, marked the quiet beginning of its transformation — one that would gain momentum in the 1990s.

What to look for today

• Résidence Grancanal 48-58 Quai de Jemmapes : built in 1977 by Pierre & Simon Epstein in a modernist style, this striking mid‑century complex with two high-rise towers and pilotis reflects the architectural language of the 1970s and marks the early phase of residential reoccupation after industrial decline.

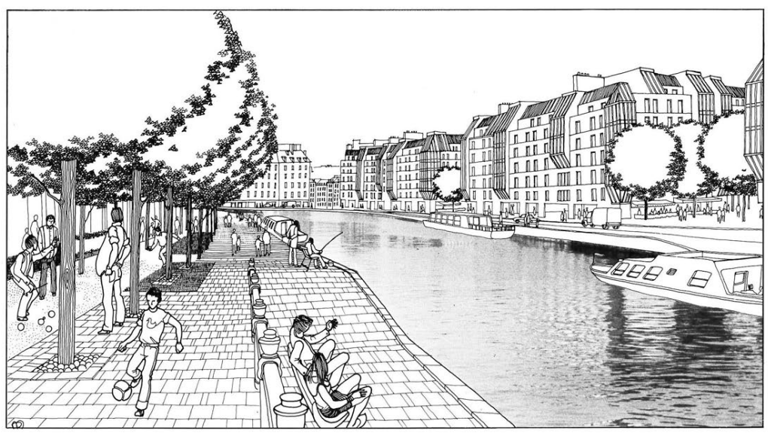

5. Revival and Reinvention (1990–early 21st century)

In the 1980s and 1990s, urban planning studies began to reimagine the canal’s role in the city. Most former industrial sites —particularly concentrated in the northern section— were cleared and replaced with new residential and office buildings— while a few structures were preserved and repurposed. The canal was officially listed as a protected historic site in 1993, paving the way for broader requalification efforts. These included the transformation of vacant land, the rehabilitation of select buildings, and the gradual introduction of vegetation. Green corridors, planted embankments, and tree-lined paths helped soften the canal’s hard industrial edges, making it more accessible and welcoming.

In 2004, Point Éphémère opened as a multidisciplinary arts venue, marking a turning point in the canal’s cultural reinvention.

What to look for today

• Modern housing and offices : developments in the northern part along Quai de Jemmapes and Quai de Valmy, such as the between 148 and 182 quai de Jemmapes reflect the urbanism of the 1990s and 2000s — functional, mixed-use, and designed for density.

• Point Éphémère’s cultural skin : murals, posters, and installations animate the building’s exterior, preserving its raw shell while reinventing its purpose.

• Street art : the canal’s walls host a rotating gallery of urban expression, reflecting the neighborhood’s creativity and its investment by artists since the 1990s.

The Canal as a Fragment of a City in Motion

The Canal Saint-Martin is more than a pleasant walk — it's a space shaped by Parisian ambition, tension, and change. From Napoleon’s plan to improve hygiene to Haussmann’s reorganization of the city, from industrial use to cultural renewal, the canal reflects how Paris keeps evolving.

Today, it’s a symbol of the city’s reinvention: where industrial heritage meets everyday Parisian life. It’s also a much-needed green space in the center of the capital — facing environmental challenges, competing uses, and questions about waste and public access.

In 2021, the City of Paris launched a public consultation about the canal’s future. Ideas include more plants, swimming areas, pedestrian zones, and cultural events. The next chapter is still being written.

Next time you sit by the water, you’re reading a piece of Paris’s story.

Enjoyed this glimpse into the Canal Saint-Martin? Join me on a food tour to explore its stories — and its flavors. Together, we’ll decode the canal’s past and present while tasting the best of the neighborhood.

Canal Food Walk

Canal Saint Martin Food Tours & Stories

© 2025. All rights reserved.